The synagogue in Subotica (1901–3), originally designed as part of the architectural competition for the synagogue in Szeged by architects Dezső Jakab and Marcell Komor, became one of the most innovative fin-de-siècle Jewish places of worship in the Habsburg Empire. This was the first synagogue to utilize the new architectural language of Hungarian art nouveau, which expressed the loyalty of the Jews to the Hungarian nation and at the same time enabled them to break away from tradition and create a modern building.

According to the architects, the Biblical Tent in the Wilderness inspired the interior of the dome; however, it also resembles the ceilings of Polish wooden synagogues and displays forms of Hungarian folklore. This groundbreaking, self-supporting, shell-like structure is composed of a 3- to 4-centimeter-thick membrane of gypsum reinforced by wire mesh and ribs on the reverse side. This magnificent dome signals the accomplishment of the Jews in Hungarian society during this period.

The synagogue in Subotica evokes Byzantine-style synagogues, with a large central cupola and four smaller ones—actually spires on four turrets—containing the staircases that lead to the women’s gallery and reinforcing the effect of the central dome. The central cupola resembles the dome of the cathedral in Florence, while its lantern recalls that of San Marco in Venice.

Subotica’s ethnically and religiously homogeneous enclaves became increasingly mixed the closer they were to the center. The middle class lived similarly regardless of their origins, and inhabited or rented the upper floor of two-story freestyle buildings, while renting out the ground floors as shops. There were a few higher buildings. The most popular style was neo-Renaissance followed by neo-Baroque and a few slightly oriental Rundbogenstil neo-Romanesque and neo-Gothic edifices. The choice of these styles was sometimes related to the ethnic or religious affiliation of the builder/owner, with Jews favoring art nouveau, and Serbs French neo-Baroque.

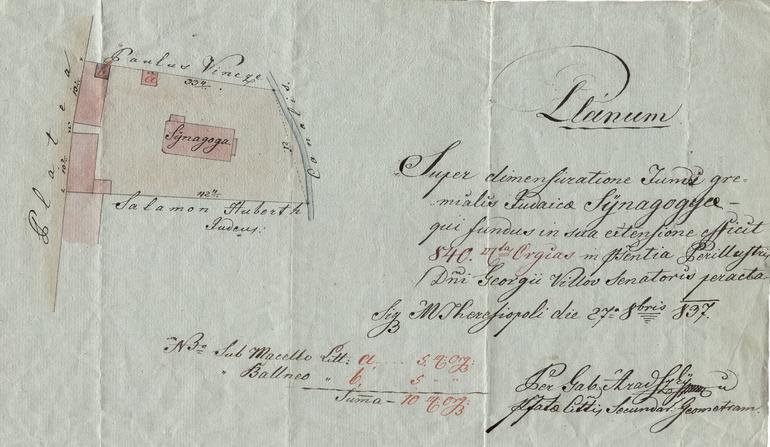

This site plan of the old synagogue with Latin text from 1837 (now in the Historical Archives of Subotica) is the only surviving visual document of the original layout of the old synagogue. The synagogue stands in the middle of the courtyard, which was customary for that period. In front of it are two street-facing buildings, probably a school, a ritual bath, and a community building that also housed the rabbi. Behind it a canalis (stream). The southern neighbor was Salamon Huberth, Judeus (Jew), and the northern one Paulus Vincze, whose lack of denomination implies that he was a Catholic Hungarian. This document proves that this was no classic ghetto, as there were Catholics on the Jewish street. Senator Georgius Vilov, who may have been a Croat, signed the document.

Designed by Budapest architects Dezső Jakab and Marcell Komor and built between 1908 and 1912, the Hungarian Art Nouveau city hall became the hallmark of Subotica, then called Szabadka. Its style demonstrates the commitment of the two Jewish architects to the Hungarian cause, during a period when national minorities opposed the melting-pot policy of central authorities. Its architectural themes follow those of the synagogue, with the addition of Freemason symbols.

Designed by Budapest architects Dezső Jakab and Marcell Komor and built between 1901 and 1903, the synagogue was the first building in the Hungarian Art Nouveau style in the city. In the style, cultural identity – Hungarian and Jewish alike – takes architectural form with bold technical innovation. Opponents of this style branded it zsidós (Jewish-like), and in 1902 the Hungarian Parliament banned its use for edifices built with public funds. Still, in regions populated by national minorities, some saw this style as beneficial in strengthening Hungarian identity.

For historic reasons Subotica’s Main Square had no church. Churches were a bit further on the tips of ethnic/religious enclaves facing toward the center, like the Cathedral of St. Theresa (far left), the Franciscan Church (mid-right) and Serbian Orthodox Church of Ascension (far right).

The 3cm-thick gypsum shell of the dome is reinforced by an internal rabitz mesh and outside ribs that enabled the creation of a tent-like shape devoid of historic traditions and statically free of a roof structure. Unlike with many period synagogues, here the dome is not suspended to the roof structure, but self-supporting.

Decimated by the Holocaust, the local Jewish community could not maintain the large synagogue, and in 1979 donated the building to the municipality under the condition that it would restore it and utilize it for cultural purposes. Little occurred until recent years, when a joint effort of World Monuments Fund, the city of Subotica, the Serbian state, and the European Union began restoration work.

This synagogue shared a corner plot with the Jewish Community Building and the Jewish School (since demolished), both designed by the architects of the synagogue. Although every square functioned as a market during festivals in Subotica, the everyday market was located here. Peasants with baskets stand in the foreground. The somewhat elongated Széchenyi Square (today Jakab and Komor Square) extends from the new synagogue to Jewish Street, and was the site where the Reformist church and the Catholic convent were built

For over fifteen years, World Monuments Fund has been committed to the conservation and revitalization of Subotica Synagogue, thanks to the support of the Cahnman Foundation, the David Berg Foundation, and the Rothschild Foundation (Hanadiv) Europe. In 2012, for the first time in decades, the synagogue was opened to the public, becoming a destination for the local Jewish population, international Jewish heritage travelers, and an expanding regional tourism audience. WMF’s long-term commitment to Subotica Synagogue’s conservation and reuse, first through inclusion of the site on the World Monuments Watch and later through project support, helped make this a possibility. The goal of this exhibition is to interpret the site’s history and to help promote greater local understanding of Subotica Synagogue and the community’s Jewish history.